The Importance of Words: Waterfall vs Agile

Waterfall methodologies are often seen as the antithesis of Agile, and therefore ‘bad’. But what does it really mean for something to be ‘waterfall’? Are you...

What do you think of when you hear the word “waterfall”?

I’m guessing many think of something like Niagara Falls (pictured above), that is, a massive water feature.

But waterfalls come in a variety of shapes and sizes. Waterfalls can be cascading, and have many levels to them, and they can even be just a few inches tall. They can have massive amounts of water flowing through them at varying speeds, or very little. The only real criteria is that water flows over a vertical, or very steep drop.

But in software development, perhaps this initial mental image of a massive waterfall has biased what we think of when we compare “waterfall methodologies” to “Agile methodologies”.

An exceptionally common response I’ve gotten to “what makes something waterfall?” is:

Big projects that take a long time

When asked why that’s bad, they often say it’s bad because large projects take a long time to provide value to the customer. So it seems, to them, the issue is the time scale. Perhaps this is the result of that mental image of the grand waterfall, or maybe it comes from this bit in the Agile manifesto:

Deliver working software frequently, from a couple of weeks to a couple of months, with a preference to the shorter timescale.

While this principle is important to Agile methodologies, the time scale is not what characterizes “waterfall” methodologies (at least, not with regards to what the Agile manifesto authors had in mind). But let’s run with that definition, if only for a bit, to see if the term then applies to many who believe themselves to not be using a waterfall approach.

So going by the manifesto, “big” would mean “longer than a couple of months”.

You might read that and go “ah! We practice SCRUM, have 2 week sprints, and release at the end of each sprint, providing value to the customer.” That might be true, but there’s two issues:

The first issue is that it might not be working software. Were defects found after it was released to the customer? How bad were they? Did any of them prevent the customer from doing what they wanted? You may have provided value, which is great, but the manifesto was about discipline and craftsmanship; not moving fast and breaking things (that’s why there’s also bits about technical excellence and maximizing the amount of work not done).

But that might be burying the lede a bit.

The second issue is that the work for that project likely didn’t start when the sprint started, nor did it likely end after that sprint finished.

The requirements and designs likely weren’t put together only once the sprint started, and when defects are found once released, it means the work wasn’t finished since now “rework” is necessary.

So as a small exercise, try to find a roadmap for your product. Find the item that took the longest time to fully deliver on in working order, and then find the time the roadmap was put together (a “created date” for the roadmap file could work in a pinch). Now, consider how long before the roadmap was put together that work started going into discovering what the customers’ requirements were that inspired the things promised in the roadmap. If you don’t know, feel free to go and ask the people who came up with the ideas in the roadmap.

What is the duration of that timeline from start to finish?

My guess is it’s longer than “a couple of months”. A lot longer.

But rest assured, the time scale is a red herring. Long term projects like this are perfectly fine in Agile methodologies (that is, you can go about a long term project while still being “Agile”).

So what does it really mean for something to be “waterfall”? To answer that, let’s take a quick look into the past.

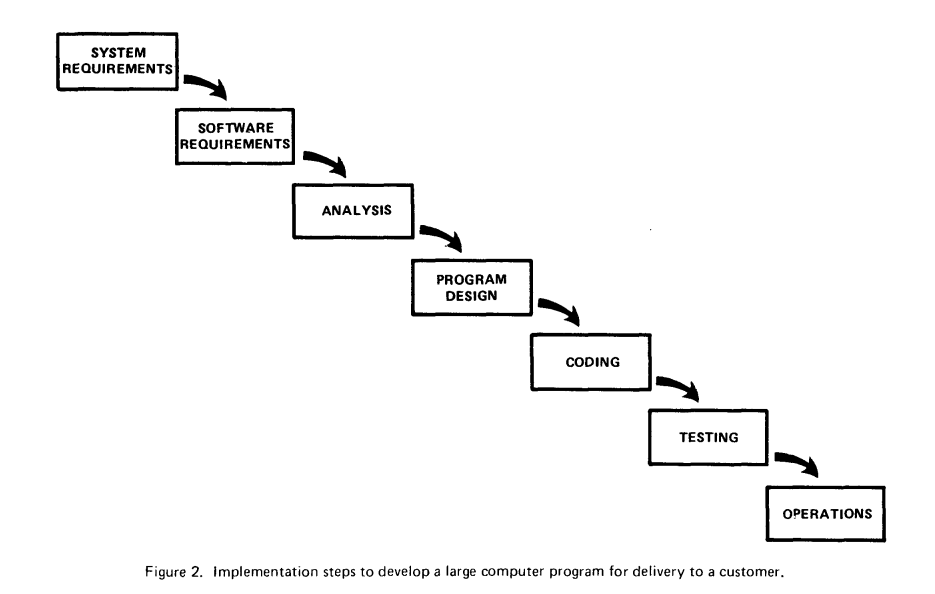

In 1970, a man named Winston Royce published a paper describing and criticizing (although, not condeming a pattern of software development that he observed. He didn’t call it “waterfall”, but it’s clear, looking at the diagrams in the paper, how that term came to be used to describe similar patterns.

I won’t go too deep into it, but Martin Fowler did a writeup on it here where he also explains the difference between Waterfall and Agile.

For now, here’s one of the key diagrams from the Royce paper that seems to have inspired the notion of “waterfall”. But I recommend reading through the paper and looking at the other diagrams as he comments on the problems (the central player being that things can go back to previous phases).

TL;DR: It’s specifically the presence of phases in the development lifecycle that characterizes “waterfall” methodologies. It’s the fact that there’s handoffs.

As Fowler notes in his writeup, Agile methodologies have the team collaborate together on sufficiently solving one problem at a time, without anyone going off to do something else for another problem until that first problem is solved. ‘Waterfall’ methodologies, by contrast, have handoffs, where one person (or a group of persons) does one activity, handing off the results of their work to another person (or group of persons) to do another activity, while the first person can then do their activity on a new problem.

“Waterfall” methodologies mimic how factories work. They operate on the assumption that one work center can do some category of work, and finish it so that the next work center can do another category of work and finish it. This is fine in a factory, where the work is the same every time, and we can iron out the kinks over time to reduce the rate of issues. But in software, the work is new every time. There are certainly lessons to be gained from certain manufacturing methodologies (e.g. Kanban/Lean), but those same methodologies would tell us that things can only be split up like this if you can guarantee the work won’t get sent back and disrupt the upstream work centers.

Certainly on the surface they might not seem so bad. In fact, many believe handoffs to be unavoidable and expect things to come back. But for those that expect things to come back, they also believe that if things come back, it won’t be much of a problem. So it’ll take some convincing to shine some light on the ‘badness’.

Let’s dig into how exactly this becomes a problem.

With phased development, it’s often set up so that different people are responsible for the different phases. But what happens in this case, when the people responsible for one of those earlier phases, hand off their stuff to the next phase? Do they just sit around doing nothing and wait for the later phases to tell them when they’re done or come back with issues? Or do they start on something else?

Typically, it’s the latter. Why? Because even without management telling them they need to be constantly working, workers will assume that expectation is there.

So what happens when those in an earlier phase start on something else, but those in a later phase need to pass something back upstream because an issue was found? They’ll either interrupt the earlier phase to get the issue resolved immediately, or they’ll try to pass it back upstream but have to wait until the earlier phase is “finished” with their new work.

Many organizations wouldn’t want those in the later phase sitting around doing nothing either, so they often respond to this scenario by pushing more things down the pipeline to “saturate” it.

It’s natural to assume that if this is the only way of going about managing software engineering projects, then maxing out everyone in the pipeline would achieve maximum productivity. But this presents a whole new set of problems.

I’m going to provide a few examples, but as I go through them, I want you to consider how each one plays off the others. Keep an eye out for feedback loops, and try to articulate how those dynamics work. For example, consider how some of these affect:

Context switching is expensive, and it adds up quickly. Every time a task comes to a worker, they spend some non-zero amount of time building or re-building the context necessary to understand and do that work. If a piece of work keeps bouncing back and forth between phases, each bounce adds more onto the total time spent context switching just for that one piece of work.

In order to facilitate handoffs, more meetings are necessary. Handoffs require coordination ahead of time to avoid a good amount of waste.

For example, less effort/time would be wasted if the designers brought their initial idea to the implementers to find out if it’s even possible before investing in fleshing out the idea, lest they have to go back to the drawing board after all that.

As the aversion to this kind of waste increases, so too does the desire for increased coordination ahead of time in order to better facilitate the handoffs and decrease the risk of things going back upstream.

Handoffs invite ambiguity regarding priority and make it unclear what the top priority actually is, unless only one thing is allowed to be in a phase at any given time (which would require a lack of passbacks). Even if you always drop what you’re doing when the true top priority comes through, you still have to context switch back to it, and then again after you finish back to whatever it was you were doing before.

The power dynamics change, favoring those upstream over those downstream. Since the whole system is based on the notion that work is to either make it through without issue, or go back upstream if issues are found, there’s a built-in excuse for those upstream when their work is revealed to be less than perfect. This lets them push subpar work downstream to whatever end they desire. For example, “isn’t that what QA is for?” or “this is why we asked the engineer if this made sense before they started implementing it.”

It’s simply easier for those upstream to come up with excuses, than those downstream.

Some organizations try to combat this by encouraging those downstream to push back and say “no”, but they also often undercut this directive with competing directives. For example, “I’m not looking for something perfect. We need something just good enough.” or “we have to hit these deadlines.” They may also undermine it by using KPIs or rewarding workers for “getting it done” rather than saying “no”. Or it could simply be undercut by giving everyone the impression that everyone should always be working.

Regardless of the nature of the dynamics, the fact remains that in a phased development process, where work flows downstream but can also feed back upstream, the pressure will continue to increase over time on those downstream.

This in turn leads to higher rates of stress, burnout, and depression as people struggle more and more to keep up.

Some organizations might try to hire more people and place them downstream to compensate, but this only slows down the inevitable in a best case scenario, and accelerates it in a worst case scenario. It also doesn’t scale linearly, even if management is willing to accept the increase in turnover it leads to.

Increased stress also means increased cortisol levels, which means people also literally get less creative, as their brains resort to old habits, rather than trying new things.

Consider how this might affect the care developers take with their implementation, the quality of meetings, or the quality of communication overall.

As the pressure increases, stress increases as a result, and as stress increases, developers and testers are less careful. As the flow of incoming work requests increases, there’s also less time for them to work on things. As a result, more faults are bound to get through.

Consider the effect this has upstream. Reports of faults from the customers would increase, and so too would demand on the developers to fix those faults. But consider how that might affect deadlines that were already committed to. What effect might missing a deadline have on the pressure applied to those downstream?

Consider how many of those faults are emergencies. How might this affect meetings for other things? Would they be interrupted, thus wasting the time spent on that meeting? Would they need to be rescheduled, thus impacting the project’s estimated timeline?

I can think of several more things that are impacted by this dynamic in a harmful way, but this blog post is getting quite long, and I think it’d be a good exercise for you to try and come up with some other ones. Think about the feedback loops that those things are a part of. Do they come back around to amplify the problem?

This system has no manageable checks and balances. It has to grow exponentially in order to relieve pressure in the areas that need it most, but that’s not sustainable. If an organization is struggling in the verification phase, they might hire more people to do that. But that means there’ll be another area that’s seen as the bottleneck.

However, what’s more common in my experience, is people develop means of having their respective phase not appear as the bottleneck, obfuscating where the most strained part of the process is. Unable to tell which area the squeaky wheel is, management may resort to the more general approach of hiring additional people across the board.

Or they may notice the increase in faults and try to hire additional developers just to write automated checks to prevent them from getting out the door. Or they could try to find some magic tool that will help them deal with the problems they believe are the source of their frustrations (e.g. “our automated checks keep needing to be updated because the locators keep changing, so let’s get a tool that promises to automatically update the locators”).

For some, this works out to an extent. But for others, it just amplifies the problems.

Equilibrium is technically possible in a waterfall approach, but it requires setting up a system that halts the flow of water upstream. This was the intention behind ‘pull’ models of work like Kanban. But the distinction with Kanban, is that there’s a focus on work centers (something can only be a distinct work center if it can guarantee its work won’t come back), not phases per se, and each one has a WIP limit.

A common part of this is that it’s all many (I would even venture to say “most”) managers have ever known. So many of them have never seen what Agile looks like, or weren’t able to recognize it if they have seen it (possibly because the team size was quite small). And when they look at what other companies are doing, they largely see more waterfall methodologies being referred to as “Agile”.

In Agile Software Development: The Cooperative Game, Alistair Cockburn notes that people are risk averse when they might stand to gain, but more adventurous when they might lose something. As he put it:

People prefer to fail conservatively rather than to risk succeeding differently.

He also notes that they may also fear the challenge of building new work habits.

I’ve seen this firsthand myself, where managers don’t want to take the risk themselves of trying out a genuinely Agile approach. And that makes sense, because if it’s no better than waterfall, they’d have wasted the effort to build all those new habits and change their mentality.

But I’ve noticed that even when managers can see for themselves the benefits, they can still often reject it, and still want to refer to themselves as being “Agile”.

I suspect part of this, though, is rooted in identity and personality, and that makes this a much harder problem to solve.

Our “identity” is how we think about ourselves, and includes our morals and values. Sometimes we attach words to it (e.g. “I’m a software engineer”), but we can never truly capture it with just words.

Personality is about our reactions to things, our thoughts and feelings, and how we actually behave. Our identity plays into this, though, as we’ll often ask ourselves what someone in a particular category we would like to identify as do in a situation. For example, “what would a good person / partner / manager do here?”

Changing these about ourselves is one of the hardest things we can do. It requires changing the way we think. It’s part of why New Year’s resolutions are so difficult to follow through on. We can’t just say we’ll start exercising if we don’t identify as someone who exercises, because we won’t be asking ourselves on some subconscious level “what would someone who exercises regularly do on a saturday morning?” We have to literally change our identity to follow through.

But if we go to those that see themselves as “Agile” and tell them they’re not, it can feel like a personal attack, regardless of the accuracy of the statement, because their ideal self (i.e. someone who is “Agile”) is now less aligned with their perceived self (i.e. how they see themselves). This is what psychologist Carl Rogers referred to as “incongruence”.

We attach all sorts of baggage to this, so it can make us feel like we are bad at our jobs, wasted our career, aren’t smart, are bad people, and so on.

Perhaps this is why, after pointing out that having handoffs means an organization isn’t Agile, and pointing out all the problems a waterfall approach yields, many taking part in it still refer to themselves as “Agile”. They may be resorting to defense mechanisms, like denial, to avoid the bad feelings brought about by the incongruence.

To be clear, while the vast majority in the software industry that claim to be “Agile” are actually practicing “waterfall” methodologies, I don’t believe they, or even the majority of them, are in denial. I would wager that the vast majority of them genuinely don’t know that handoffs mean “waterfall”.

There are certainly many who misunderstood the Agile manifesto and the distinction between being “Agile” and being “waterfall” that are contributing to the perpetuation of the misunderstanding. But there are also some who are in denial (and/or using other defense mechanisms) who are contributing to it, as well. The perpetuation of it, of course, only increases the number of people who might potentially have incongruence issues if this information comes their way in the future. It amplifies itself.

Words are important, and how we use them can impact how others understand those words. While I can point out that what many people think “Agile” or “Waterfall” means is not what was intended and is only making things worse, that does very little to actually getting people to come around. The issue also doesn’t appear to be as simple as just selling an idea really well.

We’re talking about a fundamental change in the way people think, and that’s an uphill battle. If someone doesn’t want to change the way they think, no salesman in the world can convince them to. Unfortunately, this could describe a lot of people in positions of authority.

This does, however, provide some guidance. There certainly are some out there who are open to changing the way they think, but be mindful of their feelings, as well. It would be wise to be careful while trying to figure out who is willing and considerate wherever we can, as incongruence can make us feel threatened, and responses may not be as simple as denial.

Waterfall methodologies are often seen as the antithesis of Agile, and therefore ‘bad’. But what does it really mean for something to be ‘waterfall’? Are you...

We care a lot about the word ‘quality’ in the software industry. But what actually is quality? How do we use the word in our day to day life?

It’s natural (and inevitable) for words and phrases to change in meaning over time. But what if they were chosen for a purpose, but their meaning changes eno...

A sustainable development process needs checks and balances to ensure we move forward as quickly as we can safely. But what happens when there are none?

If the developer wrote the tests for their tickets, what would QA do all day? More importantly, what are the implications of that question being asked in the...

The intent of DRY is to help us find potential opportunities for abstraction. Many take it to mean we should never repeat a block of code. However, this inte...

What is grey box testing? How can it benefit us? How is it different from white or black box testing? Are they all required? Do they dictate how we design ou...

You’ve heard it before, and probably many times. But why exactly is it the rule that should only have 1 assert per test?

Whose responsibility is it too write unit tests? Should SDETs know how to write effective unit tests?

There’s some fundamental issues with the claims that Cypress makes of themselves that need to be acknowledged. Let’s take a look at their claims and see if t...

We’ve all gotten frustrated dealing with flakiness once we start involving Selenium in our tests. But is Selenium really the problem? What can we do to solve...

The usage of React and Redux together creates fantastic opportunities for refining tests. Let’s go over one of those opportunities and the benefits it provid...

Before we can refine our tests to take advantage of React and Redux, we first have to understand what they do for us, and a little bit about how they do it.

Now we know how to maximize test validity. But how can we leverage that in other ways than just providing test results to someone else?

The validity of tests helps build our confidence in them and determines the value they add to our test suites. But what does it mean for a test to be ‘valid’?

Software tests are a form of scientific research and should be treated with the same scrutiny. To show this, let’s go over what ‘science’ is.

A collection of testing maxims, tips, and gotchas, with a few pytest-specific notes. Things to do and not to do when it comes to writing automated tests.